(Adapted from a series of articles written by Dorothy Hussey along with information from our formal history of the Gardens, A Labor of Love, now out of print.)

The Asheville Botanical Garden, originally called the University Botanical Gardens, is located on a 10-acre tract of land adjacent to the University of North Carolina at Asheville (UNCA). The evolving beauty of the Garden over the past six decades is the result of the dedication of hundreds of volunteers.

By the mid-1950’s the dream of a native plant preserve had long simmered in the minds of many individuals and groups. After World War II, population expansion led to the growth of new housing developments, businesses, and roads across the countryside. This activity destroyed magnificent trees, shrubs, and wildflowers in the process. Bruce Shinn and her husband Tom, Marjorie McCracken, and Lorene Macon had been rescuing and transplanting native plants for years. With their private gardens filling up, they envisioned a public area where threatened native species could be preserved for future generations to enjoy.

The founders of Asheville Botanical Garden were clear from the beginning that one of the primary functions of the Garden was to be a “facility for the collection and culture of native plants for the advancement of botanical science and knowledge”. It’s the collection and documentation of native plants that sets this organization apart from many other public gardens.

In 1959, a confluence of events set Bruce Shinn’s vision in motion. Asheville-Biltmore College, the forerunner of UNCA, announced that it had acquired land for a new campus in North Asheville. Ann Serota, a biology professor at Asheville-Biltmore College, had harbored the idea of a garden and greenhouse for some time, and she asked the president of the college to set aside land on the new campus for that purpose. At about the same time, Bruce Shinn asked the editor of the Asheville Citizen to write an editorial in support of the concept of a public garden. That editorial appeared on January 17, 1960, and elicited an immediate positive response. Public contributions began to arrive.

On November 13, 1960, a group of 61 civic leaders and nature-loving Asheville citizens held an organizational meeting at Seely’s Castle on Town Mountain, which was then the site of the Asheville-Biltmore College. With a common purpose and dream, they established the Asheville-Biltmore College Botanical Association. By early 1961, “… Asheville’s native plant preserve had a place, a name, a board with officers, incorporation papers, and by-laws.” Asheville landscape architect Doan R. Ogden agreed to develop the original design plans and oversee the start of work.

Clearing the land was the volunteers’ first task. It is hard to visualize today how horrible the area looked. It was partly-eroded, cut-over timberland, filled with high weeds, dead limbs and trees, invasive vines, and poison ivy, and adorned with mountains of trash. Cleaning up began in early 1961 and continued through 1962. The central wildflower trail, created in honor of Frank Crayton, a self-trained naturalist and early supporter of the Garden, was dedicated by Doan Ogden in 1961. In the fall of 1962, Ogden reported, “… Stage one is complete. One can see the results of planning, plowing, pleading, and planting.” The 1963 newsletter announced that “All paths are clear and passable … the treasury has $10,000 … and 30 percent of the area has been cleared.”

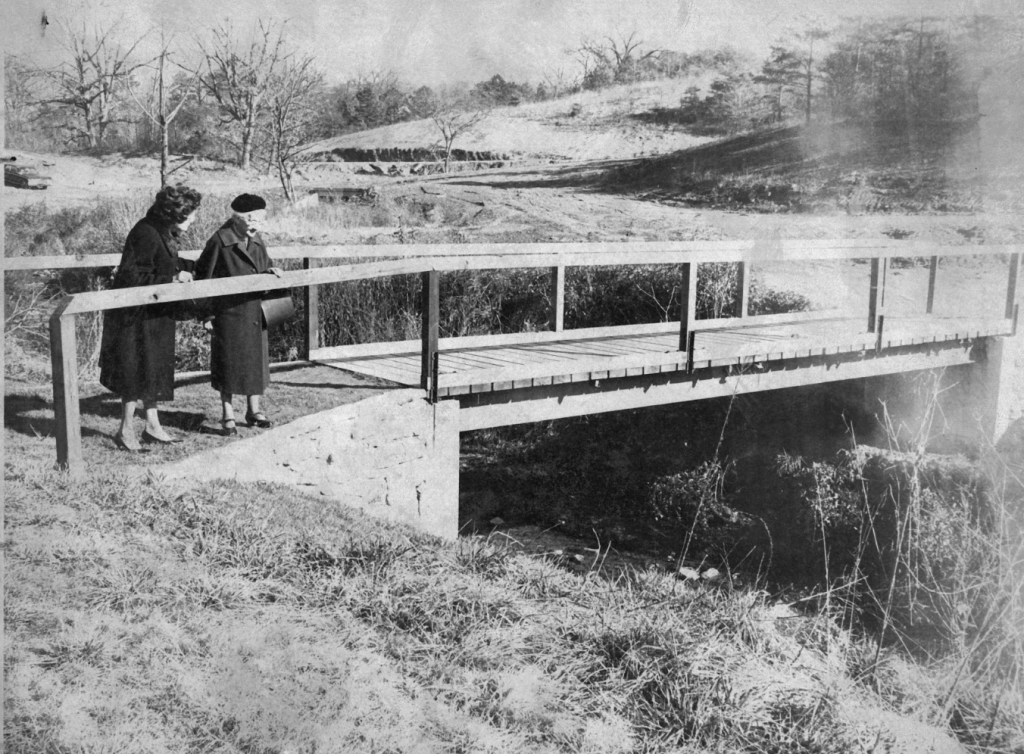

In March, 1964, planting began in earnest, and by the end of the year, volunteers had set out more than 5,000 plants. Volunteers took multi-car safaris to rescue plants from bulldozers and, by permit, to gather plants from private lands and national forests. The Green Bridge was erected across Glenn’s Creek and named for its donor, Gay Green — not for its color, although she requested that it always remain green. In 1965, an original log cabin was donated by Leona Hayes in memory of her husband Hubert H. Hayes, author, folklorist, and founder of Asheville’s Mountain Jamboree. The cabin, complete with its unenclosed “dog trot,” was moved from its original location in the California Creek section of Madison County and rebuilt, log by log, in the Garden. “Margie’s spring house” was built in 1967 to honor Marjorie McCracken, an early visionary and long-time chair of the Horticulture Committee.

The last year of the first decade saw initiation of the first “Day in the Gardens” spring plant sale and festival in May, 1969. This event has been held each year since then and has become an Asheville tradition for acknowledging the coming of spring. Numerous regional plant vendors congregate on the grounds to offer their selections to hundreds of eager gardeners who come to enjoy their first taste of buying and planning for the season.

Apollo 14 Astronaut

In its second decade, the contributions of dozens of dedicated volunteers enabled the Botanical Garden to continue its slow but steady growth. In 1970, a Founders Fund Award from the Garden Clubs of America provided for establishment of a rock garden stretching 125 feet along the road beside Reed Creek. In 1971, the Board of Directors began an endowment fund with a bequest from the estate of Beryl Fraser. In May, 1972, the Annual Spring Wildflower and Bird Pilgrimage was established by Dr. Jim Perry of UNCA’s biology department. The Pilgrimage provided lectures, bird walks, and field trips on the same weekend as our Day in the Gardens. This cooperative project offered a dynamic setting for alumni, university students, visitors to Asheville, and the community at large to celebrate the freshness of spring. On Arbor Day in 1976, the Garden was honored to become the recipient of a three-foot Sycamore planted on the grounds with special ceremonies. This distinguished tree was grown from a seed that had been taken to the moon on the Apollo 14 flight in 1971 and was one of only six planted in North Carolina that year.

In the years from 1980 to 1984, plans and construction were completed for the Visitor Center. Its need had become evident as the Garden became widely known and visited. Today, the Visitor Center is a focal point for tourists and a popular meeting site for educational and ecological groups, members of the Garden, and the local community. The Visitor Center includes the Charles M. Butler meeting room, the Garden Path Gift Shop, and offices for staff of the Botanical Garden.

In addition to its central mission of preservation of the native plants of the Southern Appalachians, the Botanical Garden has always placed great emphasis on research and education. In 1986, the family of John and Elizabeth Andrews Izard generously established an endowment fund to provide for education and research scholarships in horticulture and botany. The Izard Scholarship enables university students to pursue a project that enriches [the student’s] career preparation and adds to the scientific knowledge base.

In 1999, a grant from the Community Foundation supported an extensive project which produced the Gardens’ first formal strategic plan. At the turn of the century, year 2000, the Gardens’ marked its fortieth anniversary. In the time since its inception, what had begun as an overgrown patch of land had developed into a mature native garden. Thanks to the vision and labor of numerous volunteers and a small paid staff, the Gardens continues to evolve. Grants and donations have supported the addition of an Entry Garden, the Joiner Bird Deck, the Wilson Bird Garden, and the Peyton Rock Outcrop. An erosion control project funded by the Clean Water Management Trust Fund has fortified the two streams that traverse the grounds. The grant allowed us to expand the parking lot with an ecologically-friendly design that incorporates storm water biofiltration and a retention pond that supports a swamp-forest bog complex.